Chapter 1 – Rationale & Contextual Review

Contemporary Studio Jewellery

In her introduction to her publication Narratology, Mieke Bal explains that narratology is the theory of narratives, whether it is texts, images or cultural artefacts. The theory being the particular reality that forms the statement around which the narrative intends to express a position (Bal 1985: pp3-8). By examining the origins of contemporary studio jewellery, the narratology of jewellery as a cultural artefact, this chapter presents a definition of contemporary narrative jewellery.

As Europe entered the Twentieth Century, there was little change in the output of contemporary jewellery from the last years of the Nineteenth Century. Designs imitated old revivalist themes and Edwardian jewellery ‘…did not fully embrace the revolutionary innovations of the art nouveau.’ (Bennett & Mascetti 1989: 249). With the outbreak of the First World War, production stopped overnight with jewellers turning their efforts to the military industry or going to the front. Post war years however brought a new sense of freedom and creative expression, particularly in the world of fashion, through the work of Parisian couturiers Jean Patou, Paul Poiret and Coco Chanel. The metal workshop at the Weimar Bauhaus was under the leadership of Johannes Itten with master craftsman Christian Dell and, from 1923, was led by Moholy-Nagy. It primarily developed articles along practical lines that were for everyday use and wished to make closer links between the workshop and industry. In a newspaper article for Deutsche Goldschmiede-Zeitung, Wilhelm Lotz comments,

The Bauhaus is only interested in influencing industry. The metal workshop of the Bauhaus, as far as precious metals are concerned at all, works only with silver and prepares prototype models for serial reproduction of consumer articles. (Wingler 1969: 135).

During the 1920s the Secessionists in Vienna, Bauhaus in Germany and the Futurist movement ‘…greatly influenced the designs of many avant-garde jewellers’. (Besten 2005: MWV). Clean angular lines and geometric forms became the substance of Modernism, ‘…a world in itself. An intervention in the material, no emotion involved.’ (Besten 2005: MWV).

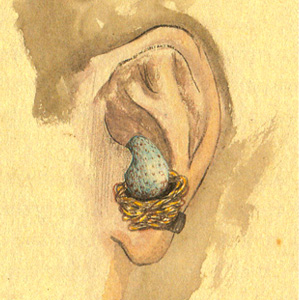

At the 1925 Exposition des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, jewellery was grouped with clothing, fashion and as accessories, showing for the first time ‘bijoutiers-artistes’, work of ‘artistic more than intrinsic value’ (Bennett & Mascetti 1989:279). During this period a further distinction emerges between contemporary fine jewellers and that of art jewellery, being jewellery designed by fine artists, not jewellers per se. Artists such as Calder, Picasso, Giacometti, Man Ray and Braque each designed jewellery, as had the Art Nouveau artists before them ‘…to make the jewel primarily a work of art.’ (Lanllier & Pini 1983: 304). The Surrealist artists, including Salvador Dali, Giorgio De Chirico, Max Ernst and Meret Oppenheim, increasingly influenced all areas of design during the pre and post war years of the 20th Century and this was popularised through the media of advertising in magazines such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. Notable examples are the set and costume designs for Diaghilev’s Le Bal, Elsa Schiaparelli’s Tear and Skeleton dresses and the small scale sculptural jewellery by Meret Oppenheim such as, Design for Ear Decoration (1942) ‘…a gold bird’s nest and an enamel egg…the ear as branches of a tree in which a bird has made its home. This work makes an enduring impression, especially because of its narrative implications.’ (Meyer-Thoss 1996: 38). (fig 2.1)

Interestingly the work is titled, a concept not generally adopted by studio jewellers in Europe until the 1960s, and addresses issues and concerns more commonly expressed by these artists through other media. Oppenheim kept a record of her dreams with the intention of investigating her own personality and ‘…to define and circumscribe her position in the world. Her dreams became sensitive instruments…a logbook.’ (Meyer-Thoss 1996: 96). Moreover, the influence of such work on contemporary jewellers at that time cannot be underestimated as it presented the opportunity to include imagery, metaphor and narrative in their work, thereby offering great possibilities previously unknown in this field. ‘Dada and Surrealism are important to a number of jewelers in particular and to jewelry in general because Surrealism emphasised the role of content and subject matter in art.’ (Drutt English & Dormer 1995: 18). This is endorsed by the American jeweller Thomas Mann who, when asked to name his influences states, ‘The Dadaists and the Surrealists. Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Cornell, Man Ray, Alexander Calder.’ (Codrescu & Herman 2001: 22).

Tiffany & Co. throughout the period from the late Nineteenth Century into the early Twentieth Century, continued to produce a quintessentially American brand of exotic and exquisite jewels. Often depicting America’s flora and fauna and Native American motifs, these strong confident works with named designers, such as G. Paulding Farnham, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Jean Schlumberger and Elsa Peretti, reflected the equally strong American economy at that time. Unlike the surrealist designs of Oppenheim, these decorative works were not meant to convey meaning or content. That said, the classic bejewelled American Flag brooch, designed 1900-10, represented the first official flag of the United States with thirteen stars and stripes and was certainly intended to communicate both celebration and a pro American patriotism. Ironically these are now more emotionally charged following the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, and current American Flags are worn commonly as lapel pins, and most prominently by the American President.

Literature of the 1950s – 60s, still regarded modern European jewellery largely in terms of ‘…symbols of wealth and social success’ (Lanllier & Pini 1983: 298). Precious materials continue to dominate and the use of precious stones encouraged work to be more decorative than speculatively artistic. Jewellers such as Gilbert Albert of Geneva, Henning Koppel working for Georg Jensen in Copenhagen and in London, Maurice Asprey of Asprey & Co., Andrew Grima and John Donald, were important designers whose contemporary work placed more emphasis on materials, form and texture, than any notion of meaning. Although by 1950, the Joint Association of Goldsmiths had been established in Denmark, which was followed in 1952 by the first of its inspirational annual exhibitions. By the 1960s things were changing in that country however,

If there was an oppressive feeling of mono-culture in the design of jewellery in the 1950s, there was a spectrum that was wider and more full of contrasts in evidence in the new decade. The economic boom, the cementing of the welfare state and the radical change in patterns of everyday life and mentality were very clearly reflected in the art of jewellery-making. (Dybdahl 1995: 17).

Elsewhere however, in addition to public demand, a factor that may have influenced the major design houses was the annual Diamond International Award. Begun in 1954 by the de Beers group in America, this became a prestigious award, and represented an important international accolade for all the award recipients. Perhaps in its own way, the Diamond International Awards helped galvanise a certain position that was to split and divide the status quo before the end of the decade.

Parallel to this activity, in the United States the post Second World War years saw the emergence of a strong studio craft movement. This stemmed from the setting up of the American Craft Council in 1939, together with a positive change in craft education. As early as 1950 jeweller Ramona Solberg was experimenting with the inclusion of non-precious found objects, such as Pendant with Earplug‘…used materials such as rulers, zippers and pencils are used, as Laurie Hall puts it, for “their metaphoric possibilities”.’ (Drutt English & Dormer 1995: 18). (fig 2.2)

Non-precious fragments become precious in the private universe she creates. Her iconography consists of unexpected and often idiosyncratic juxtapositions – glass beads from Africa, shells, milagros from Mexico, dominos, dice and found objects from antique stores and from friends. (Drutt English 2001: x).

Laurie Hall, Kiff Slemmons and Ken Cory were to be influenced by Solberg from the 1960s onwards. (fig 2.3)

In the UK, the Pre-Raphaelite and Arts & Crafts Movements (D.G. Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, Henry Wilson, Alfred Gilbert, Edward Burne-Jones), followed by the Art Nouveau Movement (C.R. Ashbee, Archibald Knox, C.R Mackintosh, Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo), saw contemporary craft work produced in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century. This led to the formation of a number of guilds and new gallery’s promoting the Craft Revival such as The Century Guild, The Art Workers’ Guild, The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, The Birmingham Guild of Handicraft and the Fordham Gallery. It also saw craft practitioners take up influential teaching posts in the newly established Schools of Art. Work from this era was certainly narrative, depicting figurative and symbolist themes and ornate floral and natural forms. These works would occasionally include titles such as Edward Spencer’s Tree of Life and Ariadne necklaces. This is the early roots of the current practice of contemporary studio jewellery.

During the late 1960s we see a link with this past coming from the workshops of Gerda Flockinger, Ernest Blyth and Charlotte de Syllas. It is not until 1971 however, that the Crafts Advisory Committee (later re-named the Crafts Council), is established and studio jewellery becomes more established in its own right. As recent as 1973, there is a cautious introduction to the exhibition Aspects of Jewellery (Aberdeen Art Gallery) by Ralph Turner, ‘This exhibition has been mounted in an effort to draw attention to the recent developments in contemporary jewellery.’ Attempting to distinguish between contemporary and modern Turner continues ‘During recent years jewellery has taken on a new dimension although much modern jewellery produced today has nothing to do with art and cannot be given any serious attention.’(Turner 1973: 1). In the catalogue accompanying the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths 1974 exhibition Seven Golden Years, Graham Hughes observes in a restrained tone, ‘Gunilla Treen…contributes some statements in plastic, hitherto never expressed in jewels’. (Hughes 1974: 3).

By the end of the 1960s and during the early 1970s, jewellers such as Gijs Bakker, Robert Smit, Caroline Broadhead and Susanna Heron, had begun experimenting with alternative, non-precious materials and concepts. Within a decade this interest would gather momentum and culminate in the seminal exhibition Jewellery Redefined (British Craft Centre 1982). This challenging exhibition was a response to the proliferation of mass produced fashion or costume jewellery on one hand, and the expensive gold and gem set work at the high end of the market, a market controlled by companies such as de Beers. Selected from an open submission, it brought together prominent and skilled goldsmiths and jewellers with the express intention of exploring non-precious materials and how we physically wear this new jewellery as a consequence. It announced, ‘A jewellery revolution has taken place in the last decade, and all the signs suggest that it is an international movement.’ (Hughes 1982: 7). The forum for such a dynamic shift was driven by the Art Schools which, through a new generation of key academics and enthusiastic student bodies, radically changed educational philosophy by questioning what constitutes notions of preciousness. This was particularly the case in the UK, the Netherlands and in Germany. The gallery circuit supported the new jewellery through exhibitions and an infrastructure of funding bodies such as the Crafts Council and the Scottish Development Agency (later the Scottish Arts Council), made it financially viable for young graduates to set up studios and workshops.

General trends have since emerged over the past twenty five years in the area of contemporary studio jewellery ‘… characterised by a concern for individuality’, studio jewellery is described as ‘… jewellery produced by individuals, working in their own studios, who deliberately control every aspect of producing a piece from original idea to finished work.’ (Game & Goring 1998: 5). One of the most important changes has been the move away from the use of precious to non-precious materials during the early 1970s, and in some cases back again, pertinent to the questioning of preciousness, value and content.

The current revival in the use of decoration and ornamentation, perhaps even nostalgia as in the work of Marianne Anderson, reflects a reaction to the austerity of post modern ideals. The re-alignment and blurring of contextual boundaries questions the very nature of the craft object and its relationship, if any, with the fine art community. For some makers, jewellery had moved from the wearable, to a photographic image of a largely unwearable object, as in Pierre Degen’s Personal Environment (1982) and the Otto Kunzli Beauty Gallery series (1984).

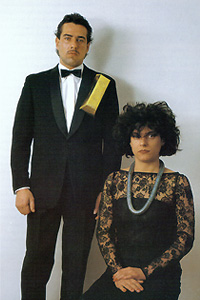

Similarly, performance had emerged as an extension to the jeweller's repertoire, although it is the quasi wearable artefact that remains central to the intellectual concept and choreography of these events, as in Otto Kunzli’s Swiss Gold – The Deutschmark (1983) (fig 2.4) and Simon Fraser’s Alchemy with a Piano staged at the ICA, London (1993). As Metcalf expresses in his discussion on ‘craft-as-a-class-of-object’, without the artefact or object the performance would remain just that, a piece of choreography, contemporary dance or ballet, and therefore impotent as a means of communicating anything of the physical object. ‘Craft cannot be dematerialised: it must first and foremost remain a physical object.’ (Metcalf 1997: 69). While this more conceptual work falls out-with the scope of this research, if we can consider what jewellery is and why we wear it, central to this is the individual, the person and the relationship between the object, the body and the person. David Poston, the maker and writer says ‘…it is reasonable to say that something that cannot be worn cannot be jewellery – being wearable is a basic qualification for jewellery.’ (Poston 1994: 1).

Contemporary studio jewellery has developed into a wide ranging and diverse art form which, although subjective to a degree, may be categorised through various terms of reference, such as; materials, form, image, kinetics, subversion, architectonic, abstraction, figuration, kinaesthetic. Narrative is also one of those categories.

Meta-narrative: Defining the Narrative Genre

The power of jewellery to explore issues of identity and personal narrative is second to none. Every time we put on clothes, and select a piece of jewellery to wear, each one of us makes a very conscious statement about ourselves and the society to which we belong. (Game 1997: 15).

‘Jewellery offers us a language we can use to tell the world who we are, what we stand for or who we would like to be. And we can use jewellery to actively set ourselves apart from the masses, thus emphasising our individuality.’ (Veiteberg 2001: 24)

The term narrative used in connection with contemporary jewellery is a construct of the Twentieth Century. With the earliest examples of the genre emerging from the United States, although unsubstantiated, the origin of its use is most likely from that country. Jewellery with a narrative content however is not a recent phenomenon, ‘Jewellery as a means of self expression is by no means a new departure. It is possible to trace its development from man’s early beginnings right up to the present day; museum collections all over the world bear witness to the fact.’ (Turner 1973: 1). These are, relatively speaking, small objects that have the potential to speak of large issues, make bold statements and question accepted values. Like a piece of poetry, this is the art of condensing, of distilling thoughts and ideas into a reduced visual representation. Meta–narrative is that act of deliberately thinking about what that narrative is intended to say, of thinking about thinking. In his lecture titled The Magnitude of the Little Dimension the Barcelonese academic and jeweller Ramon Puig Cuyas describes his personal voyage between macrocosms and microcosms: ‘Little objects can contain big ideas…I make little objects, but for me, I feel big.’ (Cuyas 2005). (fig 2.5) Cuyas’s tiny objects contain huge panoramic vistas of gardens and landscapes, seascapes and constellations, compressed thoughts within ‘little objects’.

Jewellery that communicates a sentiment or message has a long established tradition from antiquity to the present day, for example memorial or mourning jewellery most commonly associated with the Victorian era dates back to the Middle Ages. Utilising specific, symbolic materials such as jet or black enamel, blood-soaked fabric or a lock of the deceased’s hair was intended to bring the loved one closer. Royalist jewellery of the seventeenth century produced some magnificent examples. A gold and enamel corsage or hair ornament in the form of a floral spray incorporates a tiny miniature portrait of King Charles I, set under a flat crystal at the centre of an enamelled rose. It is a fine example of trembler jewellery, ‘which allows them (flowers) to move, or “tremble”, imitating the movement of natural flowers.’ (Dalgleish 1991: 37). (fig 2.6) A small number of similar pieces are believed to have been commissioned by the King and given as gifts to close friends. Eye miniatures and portrait miniatures, most popular during the 18th century, were primarily given as love tokens and occasionally worn as memento mori.

The (portrait) miniature was the equivalent of having a portrait photograph taken of a loved one – a husband, wife or child, or a sweet-heart going to war…depictions often represented the last time their families saw them alive and, as a result, they were treasured for generations (Burton 2006: 13).

Bizarre expressions of affection, the eye miniature was intended to convey to the wearer that they were being watched by the person painted, in their absence or in death. Narrative jewellery therefore, whilst being something we can observe historically, is not referred to in this way until quite recently, when meaning and content are more deliberately invested in the work.

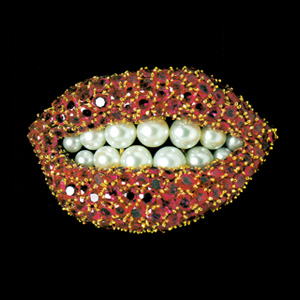

The Alvor Palace in Lisbon opened to the public in 1882, with an exhibition of Portuguese and Spanish ornamental art and religious artefacts. The ecclesiastical collections contained reliquaries, incense boats, crosiers and processional crosses. It was reported at the time that audiences were ‘…when confronted with the works of sacred art, not knowing whether to admire them or kneel before them’. (Ferreira 2005: 62). The objects could not be viewed without the potency of association intervening between the object and the viewer. The powerful religious tradition had ‘superimposed itself on the artistic object, preventing it from being seen.’ (Ferreira 2005: 62). In this sense, we can observe the communicative power of the inanimate object in everyday life. In the West of Scotland, to wear a crucifix in Glasgow may indicate a Catholic religious persuasion while a simple cross can indicate Protestant inclination. There are two major football teams in the city, Glasgow Celtic and Glasgow Rangers. Tradition has it that the Celtic club is supported by a predominantly Catholic fan base and Rangers by Protestant fans. So entrenched is religious sectarianism in Glasgow, a division dating as far back as John Knox and the Reformation of the mid Sixteenth Century, that to wear a football style scarf of green and white stripes, the club colours, will indicate support for Celtic football club and therefore presume the wearer to be Catholic, while a scarf of red, blue and white stripes will denote the support of Rangers football club, worn by a Protestant. In this context the wearing of the scarves becomes a statement of both team and religious affiliation. The scarves have become objects of powerful religious symbolism, inflammatory and divisive. On face value this may seem parochial, but its inference is embedded deep within the fabric of Scottish, and Northern Irish, society. Behavioural and national characteristics can therefore be expressed, and observed, through an object. The humble umbrella for example is a gendered object in Europe and the West, stereotypically designed and colour coded to appeal either to men or to women. In Japan they are most commonly androgynous in style, with no specifically gendered characteristics and manufactured in clear PVC. In her essay for Maker-Wearer-Viewer (appendix i), Amanda Game explores these customs further when referencing our response to the image of the heart. An enduring global symbol, it is as important in the East as in the West. ‘In Islamic tradition, it represents the essence of contemplation and spiritual life, and sacred words from the Koran are sometimes added to it.’ (Alun-Jones & Ayton 2005: 73). (fig 2.7) When the object is viewed from the perspective of Catholic Spain, it has the significance of the sacred heart and a different cultural resonance altogether to its use in the folklore of Norwegian society.

During his Maker-Wearer-Viewer Symposium lecture, Konrad Mehus expressed, in relation to his Sentimental Journey series, ‘Folk art and popular culture – something nice about these symbols that everyone understands.’ (Mehus 2005: MWV). (fig 2.8) Clearly this statement requires to be placed into context, and is dependent on the viewer understanding the nuances of the culture one is observing.

During the Twentieth Century one can see jewellery being worn as a significant means of challenging public or even political opinion, ‘The public nature of jewellery can make it a particularly suitable medium for political comment’ (Game & Goring 1998: 65). For example the button badges and jewellery worn by women of the Women’s Social and Political Union, militant suffragists, demonstrated a ‘powerful means for suffragettes to advertise their identity both to each other and the general public’ (Goring 2006: 7). Green, white and purple (representing hope, purity and dignity) were the coded symbolic colours incorporated into the jewellery by the suffragists to ‘express allegiance publicly’, and solicit support for a woman’s right to vote. Again, as Goring points out, the response of the viewer both now and then, would depend on that person’s personal perspective and one’s capacity to ‘read’ the colours.

A more recent example, in the domain of popular culture, would be the wearing of the AIDS ribbon. (fig 2.9) We may not, strictly speaking, regard this as a legitimate item of jewellery, despite its emotive impact. However it is a piece of body decoration, a pin, as significant as the Earl Haig red poppy, intended to convey meaning and act as a symbol of support. (fig 2.10) Designed by Frank Moore II in 1991 while working with the Manhattan based group Visual AIDS, a charitable organisation, the ribbon, ‘…is commonly seen adorning jacket lapels and other articles of clothing as a symbol of solidarity and a commitment to the fight against AIDS’. The small overlapping red fabric pin uses this colour for ‘…connection to blood and the idea of passion – not only anger, but love, like valentine’, (Moore 2004). Similar examples abound, such as the fashion for wearing coloured rubber wristbands, most notably during the period 2004-06. The trend was begun by the cyclist Lance Armstrong as a result of his fight against cancer and was intended to raise public and political awareness. The Lance Armstrong Foundation promoted the wearing of the yellow wristband through its charitable branch LIVESTRONG (fig 2.11)

LIVESTRONG embodied the spirit of people who have been affected by cancer. One simple gesture, wearing the yellow wristband, became a compelling symbol of strength and hope. Now, with more than 50 million people wearing hope on their wrists, I realize that these shared stories are a truly powerful weapon in the battle against cancer. (Armstrong 2002).

However, as with the Aids ribbon, one need only search the internet to establish that other charitable Trusts and profit making Company’s have subsumed the original meaning with imitations, largely reducing their impact to a fashion accessory.

Of his own collection of jewellery, Salvador Dali said

Without an audience, without the presence of spectators, these jewels would not fulfil the function for which they came into being. The viewer, then, is the ultimate artist. His sight, heart, mind – fusing with and grasping with greater or lesser understanding the intent of the creator – gives them life. (Dali 2001: 9). (fig 2.12)

It could be argued that for the makers of narrative work there requires to be both an idea and message and, of equal importance, an audience with whom to communicate the message to – communication being a key component of narrative. That said, any definition or description of narrative jewellery is, to a degree, dependent on the intention of the maker, and its subjective interpretation by the wearer and viewer. It is useful therefore to establish general categories that facilitate closer examination of, and comparison between, the work produced by different makers, working in different countries and from different cultures. It is also important to recognise in any study of narrative jewellery the time and space of any particular work. The ‘time’ in the life of the maker in which it has been created, and the ‘space’ the piece occupies in the life of the wearer in the telling of its story, referred to as ‘narrative space’ by Paul Cobley (Cobley 2001: 12).

A central issue in any assessment of narrative work is the response to it by the wearer and viewer, what Turner describes as ‘…the triangular relationship, which is generated between maker, wearer and viewer when jewelry is worn.’ (Turner 1996:76). A tangible unseen dynamic is certainly established, but surely this is not a triangular relationship as the connection between viewer and maker is never closed. The wearer becomes the intervention, the pivotal element in this linear connection, facing literally and figuratively towards the viewer rather than back towards the maker. With all narrative jewellery, as with other art forms, interpretation is personal, open to debate and influenced by the social and cultural position of the audience ‘...considering the relationship between qualities of objects and the experiences that the perceiver brings to the object’ (Crozier 1994:74). However, unlike other art forms, the object is mobile, ‘The wearer is another kind of display, moving and living, a display that can answer and look back, and also a short experienced display..’ .(Besten 2005:16). When discussing narratology, Mieke Bal refers to this relationship as ‘focalization’. The point of view or elements presented by the maker of the artefact, the wearer’s vision of the work and that which is seen or perceived by the viewer. Bal regards this relationship to be a component of the story and central to this is memory (Bal 1985: 142). Memory is accessed through vision, our way of seeing, of bringing elements together into a story ‘…through the lens of our eyes and is registered as an “image” by the brain’ (Read 1943: 37). In his publication Education through Art, Read discusses memory as a faculty that allows the viewer to retain and recall an awareness of previously viewed objects, the ‘…furniture of our minds’, thus allowing connections to be made between previous and current experiences. It is through this perception and association that the wearer is empowered to take ownership of a piece of work.

Inherent in the human condition is the need to find meaning in our lives. Contemporary narrative jewellery has the capacity to engage us on many different levels, to crystallise and encapsulate some of that meaning through a range of emotional and emotive subjects. ‘In excess of their own materiality and formal qualities, objects made in this mode have often strong narratives inscribed, which are concerned with the symbolic and emotional investment we all have in the objects we make, wear and love.’ (Astfalck, Broadhead & Derrez 2005: 19). Bernice Donszelmann states that we must understand the context of a developing tradition of narrative jewellery,

As a strand of jewellery making practice, narrative jewellery takes as one of its starting points the relationship between jewellery objects and meaning. A work of jewellery is not only a valuable object in terms of its craft, beauty and materially quantifiable worth. Within narrative jewellery the jewellery object is acknowledged and, in fact, embraced as an object of non-proper values…which find their source in emotional and psychological investments. (Donszelmann 2005: 9).

Ramon Puig Cuyas takes the same position, ‘All works of art is a container in which the artist has deposed his ideas, emotions, doubts, experiences, impressions, and definitely a part of himself, in the intention of reconnecting it all.’ (Cuyas 2005: MWV).

It is an important aspect of this genre that the objects communicate, connect and interact with the individual. ‘Such objects can be used as devices for the visible transmission of messages, a way of communicating by means of visual signs and signals.’ (Astfalck, Broadhead & Derrez 2005: 19). But what also of the viewer’s view of the wearer? What does the wearing of a piece of narrative work say of the wearer, is our perception of that person altered as a result, do we ‘view’ the person differently? In a similar sense do we, for example, respond differently to someone wearing flamboyant clothes or extravert spectacles, as opposed to the ordinary – do they appear more interesting as a result of these visual cues?

Describing his own work Manfred Bischoff says, ‘These jewels are my songline, and perhaps someone will feel a sense of recognition.’ (Turner 2005:19). (fig 2.13) The American writer Susan Grant Lewin describes narrative as ‘…jewelry that tells a story, whether based on fact, dream, or fantasy.’ (Lewin 1995: 25). According to the Oxford Dictionary, to narrate is; ‘to recount, relate, give an account of. Narrative is; an account of narration, a tale, recital of facts, a story.’ Implicit in this research therefore is the human need to communicate, to tell stories. Cobley states ‘…. why is it that humans have such a strong propensity to think events in a narrative form. Is it a deep-rooted psychological impulse, or is it cultural habit?’ (Cobley 2000: 21). Clearly, cultural influences play a large part in the style and range of narrative jewellery identified within the framework of ‘time’ and ‘space’ and as such is essentially anthropological in nature. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

Most commonly, contemporary studio jewellers will exhibit their work in the public domain through the vehicle of the contemporary gallery, museum or temporary installation space. An audience is invited to attend, engage with and respond to the work’s exposure. Can the work in this context 'speak' for itself or is a verbal or textual narratology necessary? Of her customers at Galerie Marzee, Marie-José van den Hout says, ‘It depends, if the message is clear nothing has to be explained. Mostly customers like hearing more about the work. It really fascinates them…they make all sorts of associations, to fit things into (their) own life.’ (Hout 2004). It is ultimately the maker’s choice to show their work in public, so the importance of recognition and a response to the works content is therefore actively sought and desired. However some makers feel this need for explanation is unnecessary and that there is a degree of responsibility on behalf of the viewer to react to and engage with the work, ‘We are pleasing our audience – afraid that we are not understood.’ (Peters 2005: MWV).

Strong motivational factors in the production of narrative jewellery would generally indicate that makers seek a response to their work through a need: to comment on the human condition; to communicate, and connect, with others; to have the narrative interpreted or understood at some level by the viewer.

There requires to be recognition, and within any response lies the potential for the viewer to ‘…construct a viewing methodology’ (Moignard 2005: ix), to access a personal schemata which allows a meta-narrative to evolve. (fig 2.14) Central to this is the wearer.

Whatever the maker thought he or she meant by the artefact is one component in what becomes a network of intentions and readings generated by the wearer and the viewers; all the work in the exhibition (Maker-Wearer-Viewer) has that starting point, and a large part of its fascination is that its meaning cannot remain static. (Moignard 2005: x).

For the wearer therefore, there exists the opportunity to interpret the work using a personal frame of reference, a specific set of values and through this personal interpretation, there is cognitive interaction with the object, and perhaps indirectly, empathy with the maker. As in the narratology of text, there are layers which the ‘analyst’, as opposed to the ‘average reader’ described by Bal, can interrogate. (Bal 1985: 6). The wearer and viewer also bring a certain ‘contamination’, a perception of the maker’s intention based on his or her own personal experiences. The desire of the wearer to make his or her own personal statement is certainly significant, and enables the wearer to become part of this process of communication with a wider audience.

Robert Baines endorses this ‘network of intentions and readings’ when responding to the work of Karl Fritsch,

The Karl Fritsch finger ring triggers memory. It turns the head of the owner, the wearer, to recollections of previous events, people and associations. Though the viewer may not personally know the ring, Karl Fritsch draws one to a subconscious process. We are reminded of similar rings and associations with people - Grandmother, mother, sister, and a loving friend, the implant acts as signage to reveal a subconscious process. (Baines 2001: 132).

‘Of course for jewellery to tell its story, it needs a wearer, who is an active participant in the narrative. By taking the object out and about into the wider world…the wearer becomes the positive interpreter of the work of the jeweller’ (Game 2000: 1). In literature, narrative accounts have a ‘speaker’, an agent through which the text is narrated. A text, quite explicitly, has a story or series of events that may be defined as a journey through time from A to B, simplistically; it has a beginning, middle and an end although not necessarily in that order. No such narrative journey is made by a piece of jewellery, it has existence, is self-contained and may not even offer the assistance of a title which could allude to its content. However, neither is it merely one-dimensional. It is the audience who continues this journey by interacting through the wearer and connecting with the work through cognition, memory and interpretation, thus completing the narrative sequence. As Liesbeth den Besten observes; ‘Jewellery is quite different from fine art, while being mobile…the wearer is a moving display… a sign on the body.’ (Besten 2005: MWV).

Since 1997 Marie-José van den Hout, Director of Galerie Marzee in Nijmegen has, through a series of ongoing exhibitions, documented the wearer’s response to contemporary jewellery through the choice women make when selecting the jewellery they wear. Invited to select pieces from her large personal collection, participants then comment on their emotional and physical response to the wearing of the work. The exhibitions are thematic either through geographic location such as: Sieraden de keuze van Nijmegen – Jewellery Nijmegen’s Choice, Jewellery Roermond’s Choice, Jewellery Amerfoort’s Choice, etc., or by profession as in Jewellery - The Choice of the Euro Parliament. Through the resulting publications, it is striking how empowered the participants become, how quickly the work is re-interpreted according to the profile and professional background of each wearer, ‘They are about personal identity, about self-consciousness, about believing in your own choice, and showing who you are and what you stand for.’ (Hout 1998: 4). The wearers take ownership of the jewellery.

During the panel discussion of the Maker-Wearer-Viewer Symposium at The Glasgow School of Art, Jorunn Veiteberg observed,

This understanding of narrativity, it seems that there’s a bit of uneasiness with the concept (of) narrativity. Personally I feel very pragmatic about it. It’s a concept we use when you talk also about narrative ceramics, about narrativity in literature. You could define that more precisely as a concept to work with also in jewellery. It doesn’t mean that not all other types of jewellery doesn’t have the history or is not a sort of language, but you could actually define it more strictly as one kind of tendency or one direction within jewellery. But we haven’t really done that. (Veiteberg 2005: M-W-V).

As stated in the introduction, and expressed here by Veiteberg, no adequate interpretation of narrative jewellery exists. Seeking an exact definition of the term narrative in relation to contemporary studio jewellery would, in one sense, undermine the very nature of that works openness to interpretation. There are however overarching qualities that together define the genre which is hereby offered as;

A wearable object that contains a commentary or message which the maker, by means of visual representation, has the overt intention to communicate to an audience through the intervention of the wearer. (fig 2.15)